The Final Years! Nothing for Henry but endless anguish, fears and tears!

Despite the formidable alliance arrayed against him, King Henry II would prevail. A lesser man might have sued for peace but not the great-grandson of the Conqueror. Henry conducted an extremely successful campaign, deploying an effective defensive strategy, decisively beating the Bretons and his nemesis, Louis, the King of France in the French theatre. He skilfully defeated the opposition in England where the Scot, King William the Lion was attempting to expand his territory.

William I of Scotland

‘In England, the Scottish Lion decided that he would roam!

He wished to make the land of Northumbria part of his regal home!

His intentions were ignoble and foul!

Into battle, he led his men with a fearsome growl!

Captured at Alnwick by an English knight’s equestrian trick!

He was tied by the feet and dragged at the rear of a horse, enduring many a kick!’

The proud King of Scotland’s lofty ambitions would end in ignominious captivity. The ‘Lion of Scotland’ was quite literally done with roaming; he was packed off over the channel to Henry’s castle at Falaise in Normandy where he was caged for five months.

The castle at Falaise.

Henry had won a momentous victory which established his hegemony across the continent. Although the rebellion was over, the brood were still brooding.

‘The eldest son, his father’s pride and joy!

Found that the life of a powerless king did fearfully cloy!

He demanded of his father what he thought was his by right!

He gathered his forces and proceeded to take up the fight!’

The eldest of the litter, young Henry, would simply not lie still and in 1183 got up on his hind legs to claw at his father once again. The ‘Young King’ rebelled again and during the course of his destructive tantrum, he plundered the rich shrine at Rocamadour. The reason for this apparent sacrilege was not engendered by a desire to defile, but by the dire necessity to pay his mercenaries. This being done, he then then fell gravely ill with dysentery.

The shrine of the Black Virgin at Rocamadour.

Realising that death was near and thus his ambitions at an end, young Henry became racked with contrition and sent word to his father to come for one last visit of reconciliation. The young man requested that he be laid on a bed of ashes with stones laid at his head.

‘Ashes to ashes!

‘Dust to dust’!

This was the mark of the penitent, a stance that his father had himself adopted after the death of Thomas Beckett. Young Henry felt that, given the considerably less than satisfactory circumstances, this was the only possible manner in which to greet his father.

Alas, the old king suspected a trap and declined his son’s invitation to visit, but nevertheless he sent him a sapphire ring once worn by his grandfather, Henry I as a sign of forgiveness. Young Henry died on June 11th 1183 and by doing so he united his parents, the ill-matched Henry and Queen Eleanor. They who had quarrelled fiercely for so very long, heartbroken and languishing a great distance apart, they were nonetheless totally united in an all-consuming grief at the death of their son.

The final days.

Henry’s problems with his sons were far from over. His unloved son, the treacherous Geoffrey was killed on August 19th 1186 in Paris aged twenty-seven. The unfortunate prince had become unseated during a jousting tournament and was trampled to death underneath the hooves of the horses.

Knights Jousting.

There was speculation that Geoffrey was not in Paris solely for purposes of a sporting nature. It has been suggested that he was visiting the King of France, Philip Augustus with a view to hatching yet another plot against his father. Geoffrey’s untimely passing appears to have engendered little, if any mourning at the the family home, Chateau Chinon where life continued curiously uninterrupted. Geoffrey’s wife would be delivered of a son some six months after the fateful tournament.

Then there were but two!

This of course left two sons, heirs legitimised by virtue of the the sanctity of marriage. These were the thirty-two year old accomplished warrior and proven ruler of Aquitaine, Richard and his younger brother, the callow inexperienced youth, John aged nineteen.

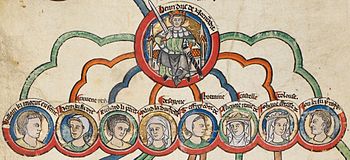

Henry and Eleanor’s children, as they were.

All of the boys died young and the youngest, John would live the longest.

Endgame

Despite his father’s efforts, Richard had not been rehabilitated after the debacle of the ‘Great Rebellion of 1173’ and there had been further trouble following the death of the ‘Young King, ‘ Henry .

Richard in familiar mode.

It was now in 1189 that matters came to a head and the long saga of family feuding would come to a sad end. With his older brother dead, Richard regarded himself as the sole heir to his father’s vast empire. King Louis VII had also died and his son Philip Augustus had ascended to the throne of France. The cast may have altered a little but the drama continued unabated. Richard now began to have reason to suspect that his father intended to disinherit him in favour of brother John. He was encouraged in this line of thinking by the King of France. Philip wished to manipulate the family feud with a view to eventually incorporating the Angevin Empire into the kingdom of France.

Richard now demanded full acknowledgement of his rights as heir to the Angevin Empire but was rebuffed by Henry. The son now decided on action and was enthusiastically supported by Philip.

Whilst having been stricken with sickness at his home town of Le Mans, Henry was faced with an attack from Richard aided by Philip. In an attempt to counter their advance, Henry had the buildings outside of Le Mans set alight. Unfortunately for Henry, at a most inopportune moment the wind changed, and the flames began to engulf the town itself. Henry had no choice but to flee and from his vantage point on a nearby hill watched helplessly as his beloved birthplace was devoured by fire.

Already physically unwell, the episode at Le Mans had served to greatly undermine his emotional state and Henry agreed to a parley at Tours. Here the old king, so sick that he could scarcely stand, met with his son for the last time. It was hardly a joyous reunion and Henry did not conceal his feelings of resentment towards Richard. Nevertheless, he conceded all of his son’s demands albeit through gritted teeth.

His strength rapidly slipping, his mind shrouded in sorrow and harbouring notions of vengeance, Henry retreated to his sanctuary at Chinon. There in its hallowed halls, Henry lay supine and took stock of this veritable wheel of misfortune which had trapped him in a ghastly circle of unimaginable misery. Perhaps he comforted himself with the thought that no further ill could possibly befall him. However, in this he was mistaken.

Here in his darkest hour he learnt that his youngest and favourite son, John had also deserted him. This would prove to be the cruellest and quite likely the mortal blow. The old king turned his face to the wall and uttered:

‘I care no longer for myself or anything else in this world.’

Henry would die on July 6th 1189 aged 56. He was buried at the Abbey of Fontevrault close to Chinon where Eleanor and Richard would later join him.