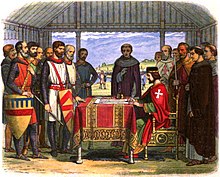

England under Simon de Montfort.

Monty, standing high above all others in the realm including the king. However, it was not to last.

The king of England was now a captive of one of his own barons; a fate which had not befallen any of his Norman/Angevin predecessors. Henry engulfed by unbearable indignation, could only reflect upon the situation with sullen stoicism. The fact that it was his own brother-law who was the culprit simply added insult to injury.

‘I, Henry of Winchester, an anointed king, now forced to obey law made by my hated brother-law!’

There is no doubt that Henry must have been angry with his son, the Lord Edward, for failing to stay on the field at Lewes and allowing Monty his opportunity to attack the royal forces in such an unexpected fashion.

‘You! My heir, Eddy proved yourself that morning to be really quite unready!

Your task was to stand foursquare with us and keep the royal flank steady!

But you could not resist the opportunity to chase those cockney knaves and put them to the sword!

Now shameful captivity for us, the royal family is your well-earned reward!’

Listening to his father prince Edward, head bowed and taciturn, mulled over his mistake and resolved to learn from it. He was intent on turning the tables on the hated Monty. In the meantime, the royal coats of arms, as the premier symbol of national authority were replaced by those of Monty.

The coat of arms of Simon de Montfort.

Symbols have their merit, but action is required to sustain their visual significance. Monty began to implement his reforms. The Great Council, or parliament as it was known, had long been comprised of the great barons and senior clerics. However, the one that met in January of 1265 was different from those which had preceded it. Monty’s parliament included two knights from each of the shires as well as two burgesses from a number of the prominent towns. These towns included the cinque ports, one of which was Hastings in East Sussex

The seal of the barons of Hastings.

These reforms had far-reaching consequences for the development of the English political system and sowed the seeds for the modern British parliament.

Of course Monty claimed that he was acting in the name of King Henry, but no one was fooled, all were aware that the king had abhorred the Provisions of Oxford. The Palace of Westminster would never seem the same again to Henry. He was now forced to linger away from the levers of power in his painted chamber at Westminster. Many might see his residence as a sumptuous palace, but to Henry it was as the cruellest of dungeons. From here he could hear Monty’s haughty tones as he spoke to parliament as virtual ruler of the realm. The painted walls of his chamber must have been awash with royal tears, no king of England had ever known such shame.

The King’s (Painted) Chamber at Westminster built by Henry III

Not only had Monty curbed the powers of the crown, he had installed himself as the de facto king.

‘De facto, de facto? Does this means that Monty is now virtually the monarch?

Yes! Yes! This is now an inescapable fact!

But the prince Edward, mindful of his birth right as heir, would not be slow to act!’

Prince Edward, his quick mind festering with the bitter memory of Lewes and his father’s resulting humiliation as being king without power, was bent on vengeance. He quite literally felt his father’s pain. Only de Montfort’s death could erase these foul memories and rectify the dreadful situation. The prince, although being held captive, was allowed to hunt in the forest with his guards. One day in May, 1265, out hunting with hounds, fine horseman that he was, Edward outrode the guards and made his way to Wigmore Castle, seat of his ally, Roger Mortimer.

A reconstruction of Wigmore castle.

The time was right, Eleanor, his mother was in France preparing for an invasion of England courtesy of King Louis IX of France.

King Louis IX of France.

Perhaps even more importantly, de Montfort had alienated a number of his key supporters, principally the powerful de Clare family, and they were ready to switch sides. The grand plans of Simon de Montfort were about to unravel.